|

| Photo by Wasim Gazdar Photography |

Last month, Pakistan’s Prime Minister Imran Khan assured that the country’s economy was on the path to recovery as the pandemic’s intensity lessened. The state has adopted measures to curb the virus and mitigate its disastrous effects, including imposing lockdowns and introducing economic relief packages. However, Pakistan’s Covid-19 response is largely missing one half of its population: women. The pandemic’s disruptive impact disproportionately affects women and any recovery failing to incorporate an intersectional, gendered approach is incomplete. This blog provides a summary of the gendered economic impact of the pandemic, critically analyzes Pakistan’s major covid-19 response strategies with respect to women and finally explores possibilities for remedial strategies. It is also important to remember gender as a spectrum, with women being one marginalized gender focused in this blog.

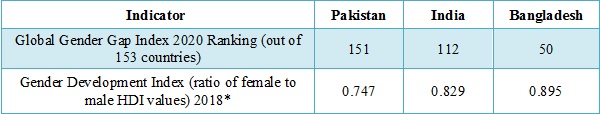

In order to understand COVID-19’s compounded effects on Pakistani women, it is important to know the country’s existing multidimensional gender inequalities that make women and girls particularly vulnerable to the pandemic and its effects. The table below provides some context, illustrating Pakistan’s performance on two global gender equality indicators. India and Bangladesh, countries with similar socio-economic characteristics and a shared history with Pakistan, fare much better in comparison on the same indicators.

|

| *Higher ratio value demonstrates greater gender equality. |

| ||

Figure 2: Statistics on female employment (source: Pakistan Labor Force Survey 2017-18; Pakistan Employment Trends 2018) |

Figures 1 and 2 provide some statistics on these conditions. Time spent in unpaid domestic, care and volunteer work by Pakistani women is 10 times higher than men and more than women in both Bangladesh and India (figure 1). These numbers are likely to be greater with increased domestic responsibilities (health, elderly and child care) as a result of the pandemic. As the time spent on care work increases, women’s ability to participate in the workforce decreases. The World Economic Forum examined this correlation for a host of countries, finding that the greater the proportion of unpaid domestic work per day, the lower was female economic participation and opportunity. This suggests that the existing very low female labor force participation in Pakistan (20%) is likely to drop further unless targeted efforts are made to counter this. Care work also limits women’s ability to adjust to the changing circumstances, such as carrying out work remotely. Additionally, a greater employment of women in vulnerable jobs (figure 2) means weaker contracts and poorer work conditions. This means women are more susceptible to the layoffs and income declines consequent of COVID-19.

The pandemic’s gendered effects have consequences extending beyond the women themselves. For instance, higher female absenteeism and drop-outs in schools and decreased female labor force participation have been known to adversely impact healthcare (for women and children both), economic growth and incidence of child marriage amongst other consequences. In countries like Pakistan, where harmful gender attitudes and norms already threaten the safety and survival of women, these effects are expected to be far worse.

The Pakistani state has undertaken some measures to

combat the virus and its effects. Its response includes complete

lockdowns, partial

or smart lockdowns in virus ‘hotspots’, mobilizing the National Command and Operation Centre to

coordinate efforts against COVID-19 and disbursement of a one-off payment of

PKR 12,000 under the Ehsaas

Emergency Cash fund. Additionally, the State Bank reduced

interest rates by 4.25 percent within a month of the

lockdown (the rate presently

stands at 7 percent) to incentivize employers to retain workers and pay their

wages. Other

concessions provided by the state bank include schemes

such as concessionary refinance and extension of loans.

However, the state has demonstrated barely any sensitivity to gender in policy design, despite the aforementioned disproportionate effects of the virus and preventive measures on women. The National Action Plan for COVID-19 has no recognition of gendered or intersectional impact in either its goals or its objectives. Without recognition, it is unlikely actual action on the same will materialize. This is already evident from the lack of female representation on the various committees established to implement the plan. One research found women represent only 5.5% of these committee members nationwide, with a total of 253 men and only 14 women in COVID-19 response committees. Trans people, although now with rights on paper, are completely absent from these plans and bodies.

There are no economic concessions targeting women, such as financial schemes for female entrepreneurs or public procurement of items such as personal protective equipment from women-led businesses. In fact, there is little to no evidence available on the implementation and positive impact of existing concessions. The Pakistan Industrial and Traders Association Front (PIAF) has said that there is “zero implementation on directives of the government” and instead a refusal to offer loans and implement refinancing schemes with several small and medium enterprises suffering. Such a failure of implementation means even if a gendered and intersectional lens is employed in design, there is little hope for its benefits materializing.

Perhaps the only

pro-women policy by the government is the Ehsaas program, established by the government’s

Division of Poverty Alleviation and Social Safety as a new poverty alleviation

mechanism in 2019. A reformation of the Benazir Income Support program, Ehsaas Kafaalat provided women from very poor families a monthly

stipend of PKR 2000 for 4 months beginning February 2020. Although more updated and accessible than its predecessor, the Kafaalat program

still requires significant changes to benefit the female population. This is because the program requires a notable degree of access to digital and financial resources such as

cellphones, bank accounts as well as IDs, most of which are disproportionately

unavailable to women in Pakistan. Additionally, the program relies on the 2011 National

Socioeconomic Registry (NSER) that is yet to be updated. This means no COVID-specific

targeting has been done under the Kafaalat program. Since

the targeted households are the poorest of the population they are likely to be

largely in rural areas while

the virus hotspots are mostly

identified in big cities. So, although the program’s funds will benefit recipient

women, these benefits are less likely to reach women significantly impacted by

the virus. The categories of the umbrella Ehsaas program addressing the new

poor (II and III) do not target women specifically.

For Pakistan to truly recover from the pandemic, a holistic

and intersectional approach needs to be adopted towards remedial strategies.

Existing research and literature provides several examples that can serve as

replicable models for the country. Economic

Crises and Women’s Work, a report by UN Women, provides

the examples of Argentina and Sweden, two countries whose crisis response was

sensitive to women’s employment conditions. In Sweden, this involved strategies

such as direct public employment for women as well as educational and

vocational assistance. Such strategies can be incorporated into existing

programs like the government’s employment generation scheme “green

stimulus” and provincial vocational training centers. More

importantly, Sweden’s policies were not limited to isolated labor market

interventions but involved a broader macroeconomic strategy that cultivated

better quality jobs and decent living conditions. On the other hand, Argentina’s

example emphasizes another important aspect of recovery; administrative and

legislative changes, such as enforcement of minimum wages and mechanisms to

ensure compliance. Moreover, a strong welfare state and collective bargaining

mechanisms, especially for vulnerable groups at the bottom of the wage pyramid,

is crucial for managing any crisis

and its aftermath.

Equally crucial for policy design, both during and

after the pandemic, is the collection and dissemination of gender

disaggregated data on Covid-19. A contextual analysis of such data allows for

more nuanced decision making. Furthermore, an analysis

of Ehsaas Kafalaat identifies solutions such as delivering funds directly to

women as a first step in addition to other mechanisms including giving priority

to applications submitted by women. These approaches allow program benefits to

reach more women and pave way for further action. Finally, health and safety

are crucial for survival and policies must address the atrocious neglect women

face in accessing quality services. Pakistan can also explore innovative

solutions during the pandemic such as in the Netherlands,

where midwife teams are utilizing closed hotels to provide maternity care. Of

course, all such solutions require care and precautions on part of the

practitioners.

These examples point to the various possibilities

for gendered approaches to the pandemic’s management. Pakistan’s female

population makes up almost half

of its total. Neglect of women in any policy will have dire consequences for

the country as a whole. As Pakistan’s Covid-19 battle seems to ease and

attention turns to recovery, it is imperative that women – especially those

belonging to vulnerable groups - are centered in policy design and

implementation.